10 Nov 2017

Interview

Interview with Kolbeinn Karlsson

Introduction

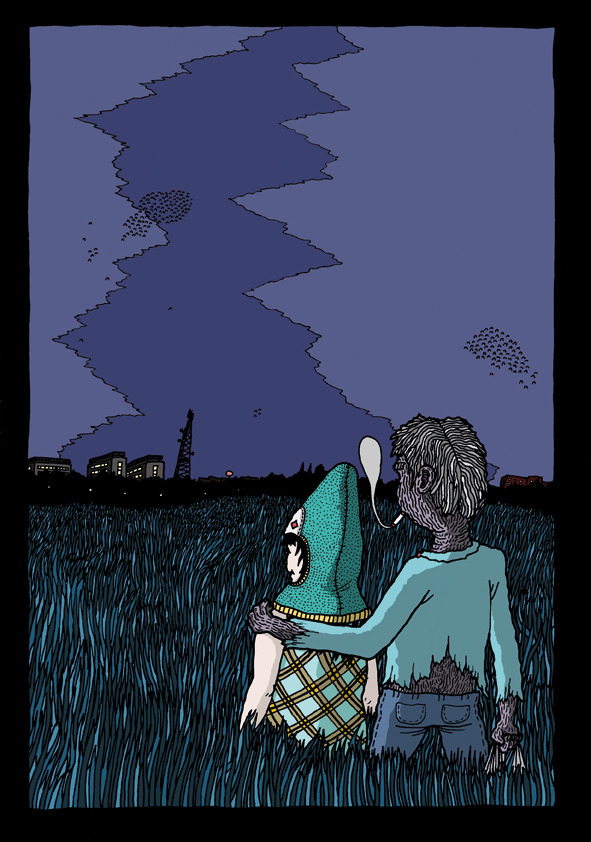

Swedish comic artist Kolbeinn Karlsson spent October at HIAP as part of the CUNE Comics-in-Residence Programme. During his time, he continued work on the follow up to 2010’s The Troll King a quirky tale of two hairy beings who flee society to live together in the wilderness. His latest work isn’t a direct follow-up, but it continues from the psychological space of the previous work. While The Troll King tells a story of misfits creating a secret world for themselves, the new project is about when that world falls apart.

Chris Dupuis: How did you get into comics?

Kolbeinn Karlsson: I was drawing comics the whole time I was growing up. I wasn’t serious about it and I was never very good at it. But then at some point it sort of crystallized that I wanted to draw. After 14, it was the only thing I could do that made any sense and I just started saying I was an artist. I had no idea what I was talking about. I was just saying it. I was going through a difficult place in my life and thinking of myself as an artist helped me get up and go. It gave me something to do and a plan for my life.

Kolbeinn Karlsson tar pits (2011)

CD: Do you think of comics as low culture? Pop culture? Something else?

KK: I like the idea of working with a medium that isn’t fully respected. There’s something a little bit trashy about comics, which appeals to me. At a certain point, I figured out a way of telling stories by placing two wide screen panels on a page. It had this special rhythm to it, but it also meant you couldn’t tell certain kinds of stories. With only two panels, you can’t have that many things happen or a lot of intrigue. It’s more like a before and after.

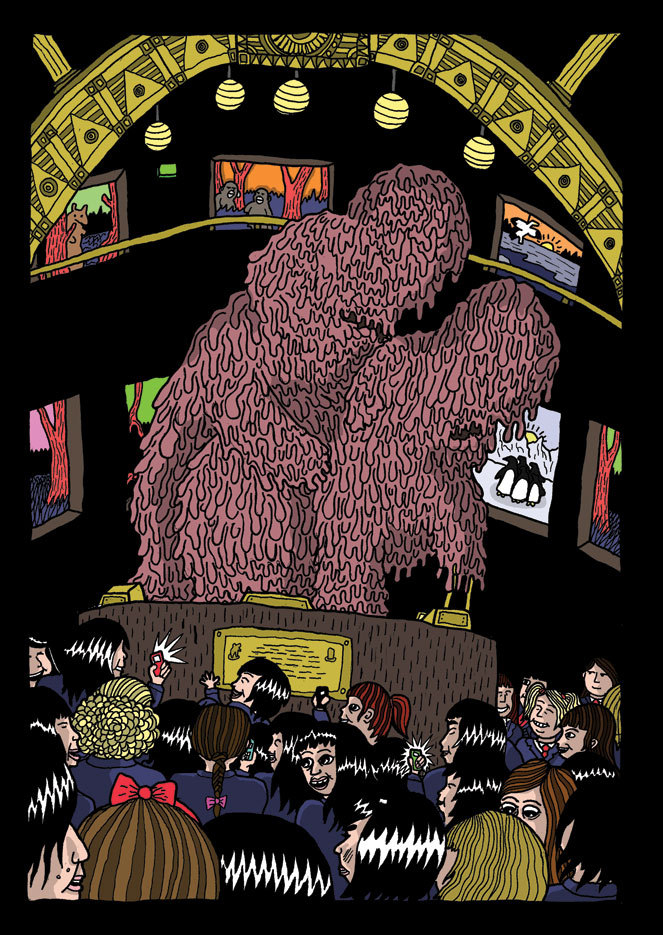

Kolbeinn Karlsson let’s wake bigfoot brown (2012)

CD: Do you feel like your sensibility is particularly Swedish? Particularly Scandinavian?

KK: Maybe. My main influences in terms of comics were. But still my work somehow isn’t. It never really fits in and it’s always a bit different from what people expect from a comic in Sweden. But I relate to nature a lot, which is part of that Scandinavian sensibility. For example, when I was trying to visualize a safe space in my first book The Troll King, I immediately came to a cabin in the woods. Thinking about what is essentially Scandinavian or Swedish, I think it’s about how one relates to the environment and the weather, more than anything else.

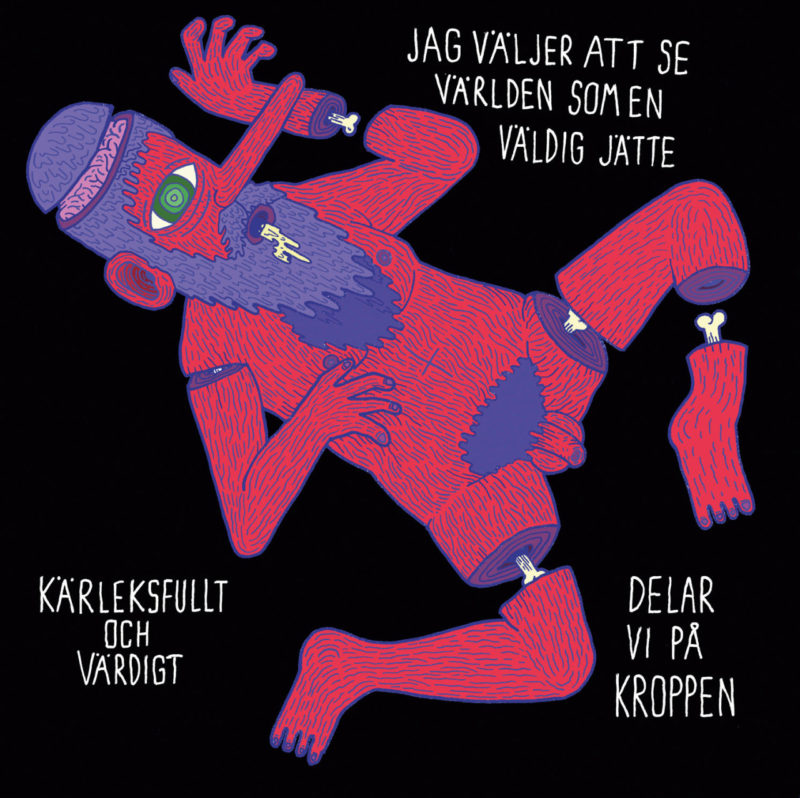

Kolbeinn Karlsson i see the world as a giant (2012)

CD: What are you doing at HIAP?

KK: I’m working on my second book, a sequel to The Troll King. That book was about what happens when you build a safe space for creatures that don’t fit in. The second book is about what happens when that bubble implodes. It’s kind of an anxious book, dark and painful. It’s taken a lot of time and the process has been a bit of a rollercoaster.

Kolbeinn Karlsson The Troll King 2 (2018)

CD: Comics often present imaginary, impossible bodies, super heroes that don’t look like real people. You represent bodies in a totally different way.

KK: I’m directly in opposition to those kinds of idealized bodies. But the drive doesn’t come from superhero culture. It comes more from Western society in general, how it depicts bodies and from my own experience of surviving in a body that doesn’t meet the standards of approval. But I’m addressing it in such a direct way. It’s more that I’m drawing the bodies that I myself want to see. With the last project I was doing, Badhusdagbok (The Bathhouse Diary) I just wanted to create this safe space on the subway. Thinking about the reactions to the project, I feel like it’s sorely needed.

Kolbeinn Karlsson Badhusdagbok (The Bathhouse Diary) 2017-2018

CD: A lot of art works have the goal of creating an aesthetic experience for the viewer. Does beauty play a role in your work?

KK: Part of it comes from wanting to subvert standards of beauty. When I present something, I want to present it matter-of-fact-ly. If I’m presenting the male body I’m not going to present this fascist idea of what a beautiful male body should be. But I’m also not going to look immediately for the opposite and try to create something that’s meant to shock. Instead, I want to present a different view of it.

Kolbeinn Karlsson Badhusdagbok (The Bathhouse Diary) 2017-2018

CD: Do you think of the nudity in your work as confrontational?

KK: My favourite reaction to Badhusdagbok was that someone said it reeks of estrogen. That says a lot about this weird place we are in with what masculinity is supposed to be right now. So much of how women are taught to act is about being pleasing for the eye. Men don’t really consider themselves the subject of a gaze. So with the subway project, it’s about showing a kind of male bodies we don’t usually see, but also just about showing male bodies in general, which we also don’t see.