27 Aug 2024

News

ANASTASIIA SVIRIDENKO: Gardens of the living and the dead

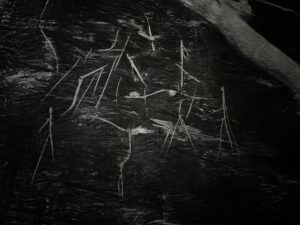

Work in progress, paper, charcoal, 4 x 2,5 m, 2024

The Ukrainian artist Anastasiia Sviridenko’s residency at HIAP Suomenlinna Studios took place from May to July 2024, during a season of almost unbearable light, lushness, and growth in Nordic nature. The island landscape is welcoming and open—warm roche moutonnées, seabirds with their babies—deceiving one into forgetting the harsh autumnal storms or piercing blizzards in the darkness of winter. The intensity of life in all its forms is nearly painful, reaching its astronomical and poetic peak at Midsummer.

Landscape

It was exactly during this luxuriant Midsummer week that I first stepped inside Sviridenko’s two-storey studio. The neatly arranged space was filled with works in progress. On the walls hung elongated paintings in strong reds and blacks. I noticed that in the back of the space, tree branches of different sizes hung from the ceiling, lay on the aged wooden floor, or rested against the old fireplace.

The studio’s longest wall was dominated by a horizontal charcoal drawing on a huge roll of paper that Sviridenko had been working on throughout her residency. The work depicted a landscape in the process of decay and decline. A long, smooth tree trunk stretched out diagonally throughout the image in a resting position. Huddled around its body were groups of smaller and slender, human-shaped twigs that were standing, falling, or already lying on the dark surface. Immersed in this scene, I felt drawn into a landscape where the outlines of my own body and reality started to violently warp.

The landscape might at first glance seem desolate and its figures doomed. The stems, trunks, and twigs seemed to be struggling against both internal and external forces, and the viewer was not sure if they could pull through. The branch-bodies had shapes that were either exaggeratedly thin and long, their limbs about to snap at any moment; twisting and bending; they seemed to move in a state of blur, an altered state of consciousness. But in their knotty, jointed, and fluid energy, the figures radiated a perseverance that challenged the spectator.

View of the artist’s studio in HIAP Suomenlinna 2024

Garden

In their white surroundings, the constellations of dry, leafless branches inside Sviridenko’s studio reminded me of a garden of dried-up plants sticking up from the snow in January. She started to collect them when preparing for her 2024 solo show Scape at Outo Olo gallery in Helsinki. Initially, the artist thought about branches as a larger sculptural element connecting her paintings and drawings, an element that could extend the surrounding Finnish landscape into the gallery space.

However, as Sviridenko began fixing her gaze on the branches lying on the ground, she started to see them as independent bodies, standing or lying. The most common position of a fallen branch, lying down, can be associated with both giving in, dying, and also desiring and receiving pleasure. A lone twig transitioned into an intangible attempt to reach a state that escapes language and attention: a life that exists beyond a human body. Sviridenko tells me how her interest in death entails interest in the body:

“The idea of death is concentrated in the mortality of the body, as there is no death outside the body. For me, death and attention to death, accepting it and living with it are a consequence of A) confrontation with the death of the Other B) confrontation with the possible death of my own, as well as collective death – I’m talking here about the experience of war. Overcoming death, actively being in the world after death, outside the confines of one’s body or even in the form of other bodies – a branch, a tree, etc.”

The garden and its life cycle carry a personal meaning for the artist, whose family had a small plot in the courtyard of their house in Simferopol. The urban surroundings made it hard to turn the plot into lush greenery, but her parents and grandmother attempted to keep their tiny space private and thriving. However, townspeople would frequently step into the garden to defecate, have sex, or just throw their rubbish in the yard. The dream of the sensuous lushness of a private garden bearing fruit and giving life was continuously contradicted by the grotesque, foul, and rotting:

“My bewilderment about the publicity of our garden and all the unattractive actions of its visitors is a clear example of the attitude towards ‘the body’ as property. Life is public. Death is public. Our garden was and is as public as anything else. I think this is a very useful conclusion for preparing for and accepting death as such. If we think of death as a transition from an individual to a universal state, when you no longer belong to yourself but rather you are everything.”

Work in progress, paper, charcoal, 4 x 2,5 m, 2024

Cemetery

In her works, Sviridenko approaches the human body as a starting point of constant transition, uncertainty, and corporeality. Lately, she has been reading the book Being with Dying by Joan Halifax, where the author emphasises the need not only to care for those around you who are dying but also to care for oneself as someone in the constant process of dying. For Sviridenko, collecting the branches and the tactile practice of working with them became an act of tending, touching the “cemetery” and its body. Attending the garden and caring for the dead led to the fusion of the two elements in the garden of “dead” matter:

“I think that collecting branches is tuning the optics of attention to the ‘body’ that has an identity and eludes it, producing itself, throwing itself out. And branches for me are more like signs (of bodies) present everywhere: in parks, in parking lots, in sewers, in foreign countries and on the roof of my house – they can come any moment from anywhere.”

In Sviridenko’s charcoal landscape, the life of the singular human body might have reached its end. But in her gardens, life just takes another form, releasing the body to another state of matter, just as rich and dense as the high summer in the landscape surrounding the studio.

“The cemetery is the garden of dead matter. In fact, there is no longer any concern for the body as a unit. The cemetery is truly an exposure of this fact – bursting, rotting, flowing, disappearing, dissolving, moving, dislocating, colour-changing bodies.”

View of the artist’s studio in HIAP 2024

All images courtesy of Anastasiia Sviridenko

Anastasiia Sviridenko is a Ukrainian painter and draughtswoman currently based in Finland. She works at the interface between figurative representation and abstraction, reflecting on existence.

Riikka Thitz is a Helsinki-based curator whose work is centred on the bodily experience of being in the world. Using landscape dramaturgy as her tool, she works with both visual and performing arts.

Sviridenko and Thitz were both residents at the Helsinki International Artist Programme on Suomenlinna Island during the spring / summer season in 2024.

Anastasiia Sviridenko’s residency is realised in the context of the Ukraine Solidarity Residencies programme.

The programme has been realised in partnership with AARK, Art Centre Salmela, Connecting Points programme, Fairres, Goethe-Institut Finnland, HIAP – Helsinki International Artist Programme, Kristinestad Art Residency, Loviisa Art Support Association, Nelimarkka Museum, Pro Artibus, Tahmelan Huvila, The Finnish Artists’ Studio Foundation, The Finnish Illustration Association Kuvittajat, and Värtsilä Artist Residency.

The programme has been supported by the Kone Foundation and Nordic Culture Point. The continuation of the programme in 2024 is possible due to the support of the Ministry of Education and Culture and Goethe Institue Finnland.