28 Sep 2021

Interview

Art residencies and sustainability: A Russian Perspective

A new three year research project Reside / Sustain: Finnish & Russian experiences/initiatives/practices supported by the Kone Foundation focusing on residency activity and its ecological possibilities has started within the Connecting Points-programme. The project examines the role of art residencies in enabling sustainable development in Finland and Russia and aims to answer questions of how residencies can provide platforms for the multiple aspects that are necessary regarding ecological action and change.

The project consists of a collaboration between three individual practitioners, Miina Hujala, Adel Kim and Angelina Davydova, each of whom brings forth their specific areas of expertise as well as connections to a wider institutional framing.

Anna Kozonina has interviewed the collaborators in the project to shed light on their backgrounds and perspectives involved.

Adel Kim. © Kim`s personal archive

The protagonist of the first conversation is Adel Kim, a Moscow-based curator who has been exploring the field of Russian art residencies both as a practitioner and a theoretician. Adel is also involved in the work of the Association of Artistic Residencies of Russia (Air of Russia).

Anna Kozonina: Our conversation will focus on Russian art residencies and the topic of sustainability understood in two different ways: first — as a way to maintain residencies, keep them working, second — as sustainable environmental development. We have two main goals: to introduce readers to what the field of art residencies looks like in Russia and to discuss the potential of residencies as actors of ecological development. But before we start discussing the field of Russian residences and the problems there, I would like to know how you came to explore this topic. Could you please tell us a few words about yourself and your background? How did you get involved in the topic of residencies?

Adel Kim: My interest started on the practical and theoretical sides at the same time. In practice, I got acquainted with the work of residencies when I was doing my master’s of art in Seoul, South Korea, and did an internship in residence at the Seoul Museum of Modern Art (MMCA Residency Goyang). It is a fairly large state residency, designed to simultaneously host about 20 artists. That internship became the main entry point to the topic: I was participating in the daily work of the residency, and I was also learning about ethical communication with artists, and exploring the rules and principles that exist in this field. When I returned to Russia, I worked for three years as a residency manager at the ZARYA Center for Contemporary Art in Vladivostok: at that time, I managed to work closely with about 60 artists.

Afterwards, I moved to Moscow to work with the Tretyakov Gallery on the launch of a new museum branch in Vladivostok, which is scheduled to open in 2024. At the same time, I didn’t want to leave the topic of residencies behind, so I took part in the organization of the Association of Artistic Residencies of Russia, which was initiated by Kristina Gorlanova and Zhenya Chaika from Yekaterinburg. At that time, Kristina was the head of the Metenkov House, and Zhenya had many years of experience as a curator of the residence at the Ural Industrial Biennale. They are both very respected professionals, who were and are leaders in the Russian residency community.

In 2019, Yekaterinburg hosted the first Forum of Russian Art Residencies. It was a logical continuation of the sporadic meetings that had previously taken place here and there but were not organized under the umbrella of one organisation or event. That year, we finally launched the AiR of Russia website, where we collected information about Russian residencies. There are a lot of similar web resources all over the world, from the Netherlands to China, but there has never before been a platform that would present the general picture of what the Russian field looks like. Information about residencies in Russia has always been very scattered and difficult to access. It was important for us to collect this information in a clear and convenient form so that it could be used by both Russian professionals and international colleagues.

In parallel, I was doing my master’s in cultural management at Shaninka School (The Moscow School of Social and Economic Sciences). There I concentrated on the study of Russian residencies and tried to find out how the field and practices of local residencies, often small and self-organised, differ from other practices which were familiar to me — for example, from the work of state residencies in Seoul. It is intuitively clear that Russian residencies have their own specificity which traces back to the peculiarities of Russian infrastructures and cultural policy.

Kozonina: Then let’s talk about that. In your research work, first of all, you try to define what an ‘art residency’ is and, secondly, to understand how Russian residencies differ from ‘international’ experiences. Yet how did the artist residencies appear in Russia in the first place? You mention that they started to develop in the 2000s, that is, at a time when Russian contemporary art was entering the institutional rails, but a noticeable increase in residencies has been observed only in recent years. How could you explain this rapid growth, given that the whole field of local contemporary art seems to be in some kind of stagnation today?

Kim: I think there were several parallel lines in the process of their emergence. The first organisations appeared in the late 2000s, and the first people who started to talk about residencies were not artists or curators but cultural managers. In the early 2010s, a Russian-Dutch symposium was held in Russia as part of the ‘Mutual AiR Impulse’ project. It was attended by representatives of TransArtists, an international web resource dedicated to residencies. That event was followed by the publication of the same name, and it was the first attempt to systematise knowledge about residencies in Russian.

Initially, in Russia, professionals started talking about residencies as a tool for the development of local territories — remote, abandoned, hard-to-reach, and in need of a creative impulse. This distinguishes Russia from many other countries. For example, residencies in the United States and Europe, as a rule, used to grow out of colonies of artists who needed solitude, a shelter from mundane everyday problems, time for creative work, and a platform for communication with colleagues, experience, and practice exchange. That is, the impetus came from artists and patrons, so the residencies in international practice are concentrated on the support and development of art practices.

On the contrary, in Russia, the conversation about residencies almost immediately focused on the development of territories, and less on artistic practices, that is, it had a more utilitarian direction. My hunch is that to some extent it was due to the fact that the rhetoric of territorial development is more effective when you need to find the money for a residency and justify its existence. For some reason, most residencies in Russia followed a similar path and began to copy the practices of their local predecessors without much regard for international experience. Many Russian art residencies are small organisations designed for short-term stays of one to four artists. Many of them are aimed at exploring the local context, so a residency in Russia is a very important tool for increasing the professional mobility of artists and cultural workers. They help you get to places that you just can’t reach in any other way. And since the residency is a flexible and easily transformable format, many people began to open them in their territories and reproduce them in their own conditions. It seems to me that the process of distribution of residencies in Russia looked like that.

© VYKSA Artist Residency / Арт-резиденция «Выкса»

The second channel of their proliferation is connected to the activity of major museums and cultural institutions. For a long time now, the ‘Masterskiye’ (‘Workshops’) in the Garage museum have been open. Soon, the ‘Svody’ (‘Arches’) workshops will open at the building of ГЭС-2 of the V-A-C Foundation. The Samara branch of the Tretyakov Gallery, and then the Vladivostok branch, also plan to open a residency. The National Center for Contemporary Art also has many similar plans.

Here’s another interesting case. Recently, I have increasingly observed that representatives of state cultural policy apparatus have started to use the term ‘residency’ when initiating events that are very far from what artist residencies normally deal with. For example, within the framework of the art cluster Tavrida, there are plans to create a residency, which in fact is a year-round educational centre for creative youth, and the project itself is associated more with creative industries, brand development and SMM practices, than with art. That is, the term has been appropriated and ‘stretched’ to represent completely different contexts. Perhaps, the positive experience of holding art residencies in recent years has given the term a completely different life and existence in different fields — at least in the understanding of those involved in cultural policy on the part of the state. I wonder if there will be a conflict in the near future due to the blurring of the concept, whether there will be a desire to defend the original meaning of the term, or, on the contrary, we will see the disappearance of the boundaries between these different areas.

As for contemporary art, I agree with you about stagnation. But the format of residencies is quite tenacious in a situation of stagnation because it is very flexible. As a rule, residencies do not organize huge exhibitions at the end, they often exhibit art in the work-in-progress format. In addition, they have less self-censorship and a little more freedom than is the case of participation in major exhibitions.

Kozonina: Let’s summarise this part. So far, you have named three types of residencies, three sources of their origin. The first option is when a territorial unit or institution working with a specific territory creates residencies for the development of the local cultural situation. The second — residencies at large museums — private and public. The third example is this strange Frankenstein, the merging of state cultural policy with the creative capitalist industry, which has nothing to do with the wave of artistic residencies and the development of contemporary art and is simply an appropriation of the term. Do I understand correctly that there are still residencies that are self-organised initiatives of art workers? They are perhaps closer to the phenomenon of ‘artist colonies’, which create spaces for private or collective work. One example is the residency ‘Camp As One’ in the Krasnodar Territory, which positions the joint recreation of artists as a kind of Gesamtkunstwerk and is not tied to the territory development. Or the St. Petersburg studio ‘4413’, which simultaneously hosts artists, arranges events, and serves as accommodation for its organisers.

Kim: These self-organised residencies, I think, appear as a response to the lack of either institutional organisation or freedom within existing institutions. People are missing the lively collaborative research process, and they make up for it by creating their own residencies.

So, yes, it is very roughly possible to divide Russian residencies into four types. The first type is private residencies or those at museums/art centres that emphasise the local identity of the area and focus on the development of the territory. The second type is residencies at large private and state museums. The third is grassroots initiatives, residencies run by artists themselves or independent curators, where the main value of participation is the opportunity to interact with colleagues, spend time together, exchange ideas, and support the creative process. The fourth type is these new ‘Frankensteins’. Although we can name one more type: residencies that work as hotels. Accommodation there is often fee-based. For example, the residency ‘Quartariata’ in St. Petersburg (which does not exist anymore) used to work on this principle. In the Moscow region, there is a hotel ‘Chekhov #API’, which also positions itself as a residency. I know that at the Academic Dacha of Repin, formerly one of the most famous creative countryside cottages in the Soviet Union, there is an opportunity to stay and work for a certain fee. In general, it is important to understand that, since the concept of residency allows for broad interpretation, we can only list the features of Russian residencies, but it is difficult to distinguish clear types.

© PolArt, Norilsk Museum (Музей Норильска), 2016

Kozonina: Let’s talk more specifically about geographically oriented residencies. What are they like in general?

Kim: Locally-oriented residencies can be quite different. Many of them have one important thing in common: they are located in more or less exotic or hard-to-reach places — places where you would hardly find yourself by chance. But they may have different institutional affiliations. There are residencies attached to local museums, to Artists’ Unions, and there are relatively independent institutions, for example, funded by private or state-owned companies. For instance, the residencies in Vyksa and Nikel, sponsored by metallurgical companies, are aimed at the development of the territory itself, and at maintaining the existing cultural activity and local communities, if any. These are small single factory towns, with a pretty meager cultural landscape. Residencies enliven them, involving people in more active interaction.

Local residencies can be gallery-based: for example, in Karachay-Cherkessia, there is a residency initiated by the Artwin gallery. Another option is non-profit organizations that work with the support of regional administrations. For example, there has long been a residency ‘Artkommunalka. Erofeev and others’ in Kolomna, in the Moscow region. It is focused on the genius of the place because Venedikt Yerofeyev used to work in the house where it is located for a while. As far as I know, this is the first residency in Russia designed for writers (recently another writers residency has opened in Peredelkino). That is, locally-oriented residencies may have different organisational structures and sources of funding. In addition to being located in hard-to-reach or just hidden places, usually far from the capital cities, they are united by a fairly similar set of conditions for artists. Such residencies underlie the ‘wave’ that occurred in the mid-2010s. Only now are residencies beginning to be more actively concentrated in large cities.

Kozonina: As far as I understood, the rhetoric of ‘development’ of a certain territory is first of all utilitarian. Since it is difficult for us to justify the support of art for its own sake, at least we can allow artists to study the local context and create works within the framework of a residency. However, if you seriously look at residencies as a driver of territorial development, many questions arise. The development of the territory is a strategic and long-term thing, and residencies are short-term programs that invite, in fact, ‘strangers’ to the territory. Can they really ‘develop’ something there? Are there any criteria for ‘development’ or is it rather the rhetoric of legitimising the existence of the residency as such?

Kim: This is a good question, for which I can’t give a comprehensive answer. Of course, residencies are not completely instrumentalised. No one conducts ‘measurements’ or compares the local situations before and after the residency is held. Even if someone tried to establish criteria and measure effectiveness, it would be difficult to say what was the specific role of the residency in the overall process. As far as I know, there are no such studies, and we can only rely on the formal reports of the residencies’ organisers. At most, the report will show how many people attended the public events. As one of the first Russian organisers of residencies Georgy Nikich, told me in an interview, the story about the development of territories and assistance to local communities is a kind of ‘project-bureaucratic mantra’ that helps to legitimise the establishment of a residency.

© VYKSA Artist Residency / Арт-резиденция «Выкса»

In addition, it seems to me that the conversation about the development of local communities is not a purely Russian thing, but rather a borrowing from Western discussions. I’m not sure we would have this discourse if we didn’t read, say, British authors. If we talk about a community, it is a gathering of people who, ideally, know each other and have a common goal. To call any people living in the same territory a local community is a big simplification. We assume that there is such a subject and we will work with it, although in reality, it may simply not exist. Of course, residencies themselves can create an environment of active residents, art lovers, or those who are somehow involved in related events. They can create a community, but it is quite difficult to say that artists come to work with already established communities. Plus, working with a community requires a certain duration and consistency: you need to return to people, maintain social ties. I think most residencies don’t do this just because they have many other concerns.

In addition, since participation in remote residencies is, first of all, an opportunity to increase professional mobility for artists, I do not rule out that it is the artists who benefit most from such trips. For locals, the constant rotation of newcomers who need to be ‘involved’ and ‘integrated’ into the current processes can be a headache.

And, of course, if the purpose of the residency is to help the locals or develop the territory, it would be nice to first ask the locals what exactly they need.

Kozonina: Let’s talk a little bit about what artists should leave to the places they come to. In your study, you mention that in Russia there is a practice of gathering collections at the expense of works created by artists within the framework of residencies. What kind of practice is this?

Kim: Residencies provide artists with some kind of material support. Almost always it includes free accommodation, sometimes — a grant, travel expenses, or per diem. Since in Russia the idea that residencies primarily exist to support artistic work is pretty weak, there is a situation in which the artist must pay the organisers back in some way. And not only by giving lectures, holding workshops, or participating in final exhibitions, but also by giving their own works. This practice exists not only in Russia, but it is very common here. In many other countries, it is considered unethical, and the fact that a residency collects works from artists can even have a bad effect on its reputation, discourage foreign partners from it.

There are many controversial points in this practice. First, the work has a market value, and it is rather doubtful to equate the cost of any artist’s work with the price of a flight, an amount of granted money, or a daily allowance. Secondly, in this case, we remove the process of purchasing the work from our relations with artists. No contract is signed, and it is not always clear how the work will be maintained or exhibited in the future. In addition, when artists first start working in a residency, they often do not know how many works and in what format they will leave to a collection because no one knows what the project will end with. Usually, the decision is left to the curator of a residency. Unfortunately, a significant part of the residencies that emerged in the 2010s accepted this practice as an adequate solution to their internal problems.

And it’s funny that the works are collected not only by private organisations or gallery residencies but also by art centres that are funded by large or small businesses. Even regional museums do this, though they have clear procedures for accepting works into their collections, so this practice may bring them more problems than benefits. Many residencies become a tool for shaping the collection of either an existing museum, a future museum, or a sponsor’s collection. The very idea of supporting an artist here takes an interesting turn. We kind of support you, but you have to leave something in return. Although it is quite wild to charge something for patronage activities. But the strangest thing is that this practice has not yet faced tangible resistance on the part of the artists themselves.

Kozonina: This can be a sign of general passivity in defending labor rights in the art sector. In Russia, the ‘professional field’ of arts is not clearly defined, often there is a feeling that the piece of art is worth nothing, there is no market, and artistic work can be exploited in any way. Although recently I have noticed more attempts on the part of artists to defend labor rights in various fields of art.

Kim: I hope that something will change soon. It is important to understand that it’s generally possible to create a collection based on residencies’ activity. But to do this, you need to buy a work of art. This should be a joint agreement between an artist and an institution, a contract should be signed. For Europe, these are common truths, for Russia — unexpected speculations. However, after this problem was voiced at the first Forum of Art Residencies two years ago, it seems to me that the situation has started to move from a dead point. For example, the successor of the art residency ZARYA in Vladivostok, now — the residency ‘Golubitskoe’ in the Krasnodar Territory, no longer collects work. Here we can only hope that this process won’t stop, and there will be more clarity and fairness in market and labor relations. But so far, this is a very characteristic feature of Russian reality.

© VYKSA Artist Residency / Арт-резиденция «Выкса»

Kozonina: You’ve mentioned that this problem was brought up for discussion at the first Forum of Art Residencies, which was held in 2019. The second Forum is planned for November 2021. Could you summarise the agenda of the first forum? What were the main issues it addressed and in which directions did the discussion around the next two years of Russian residencies go? What questions do you think are most relevant to the Russian situation right now?

Kim: The main discussions of the first Forum revolved around what an art residency is in general. It involved about 40 participants from different cities and organisations: some were already making residencies, others were just about to start. The questions were basic: what an art residency is in general, what the standards of its organisation are, how to interact with partners, including foreign ones. Many questions have been raised regarding international partnerships. For example, if we participate in an exchange program with a European residency, it is important to understand what kind of resource a Russian partner can provide. And, by the way, here the issue of collecting works is a matter of principle, since, of course, international partners are not happy if the taxes of their citizens are used to replenish private collections of Russian museums or corporations. The third day was devoted to fantasies about residencies and the invention of new formats. At the same time, we decided to create a website and publish a methodological guide on how to make residencies. I hope it will be released very soon.

The second Forum will be held in Vyksa in 2021. It is planned to open a renovated building of Soviet modernism for a residency there. There will be a large-scale conference dedicated to the topic of hospitality in the context of art, and within its framework, a separate block will be about residencies — this will be the second Forum. The conference is supported by the Presidential Grants Foundation.

Potential participants of the forum today are interested in very practical and urgent matters. Now, it is important to understand how we survived the pandemic and what new practices, lessons, life hacks, and formats of existence we’ve developed. The second pressing issue is the sustainability of residencies: how to successfully maintain your activities and be prepared for any crisis, how to survive and work for a long time. Many people are interested in the issue of residency infrastructure.

Kozonina: And what would you personally like to discuss with your colleagues right now?

Kim: There are many interesting questions related to the operational work of the residencies. For example, the most basic question is the status of the premises in which they are located. Often, residencies are situated in buildings that are not registered as residential premises. This becomes a problem when foreign artists are invited. They need to register at the place of residence, and it is impossible to do such registration in the residency itself. If it is a private territory, then the situation is not so terrible, and if it is part of a museum or a former factory or some other industrial premises, in fact, you can not live there. Therefore, often residencies are forced to position themselves as organisations of a certain type, but in fact, they are something else. They are not legally protected in any way, and I do not know how much lobbying can work here — for example, in terms of simplifying registration for residential premises. This problem affects a lot of organisations.

From a practical point of view, it is also interesting to know what new formats of work residencies have invented during the pandemic, and what useful discoveries they have made in terms of saving financial and human resources. What can we bring from this experience to our post-pandemic life? How can we support artists if we can’t invite them to the site? What are the alternatives to offline hospitality? How can they be applicable to ‘normal life’?

Also, many ‘uncomfortable’ questions that are obvious to everyone, but rarely articulated, are always looming in the background. For example, can political art exist at the expense of those it criticises? Or what is the status of residencies that are funded by large industrial companies that negatively affect both the environment and the employment situation in cities? Are the residencies in this case a tool for legitimising their activities? How do you learn to take care not only of a resident but also of yourself, taking into account how often professional burnout happens to the employees of the residencies? For the participants of the field, these questions are on the surface, but for the rest of the public, they remain opaque.

© VYKSA Artist Residency / Арт-резиденция «Выкса»

Kozonina: We have already touched a little on the topic of the sustainability of residencies. How do you assess the survivability of Russian residencies in general? To what extent are they able to maintain their existence in the long term? And what are the ways to increase their life cycle?

Kim: This is a very relevant topic for Russian realities because we constantly see how quickly new residencies appear and disappear. The fact is that in the Russian interpretation, many residencies are not independent institutions, but programs under the umbrella of other institutions or initiatives. That is, any institution in the field of art can launch a residency without spending too many resources. The residency work implies mobility, joint creativity, temporary activity — for two weeks, a month, or two. Therefore, programs arise and disappear very quickly on the basis of existing initiatives. In general, there is nothing wrong with this, but the problem is that in Russia this format is extremely widespread. It does not allow us to work for the future and gradually improve our actions. If it is a one-time project, it will most likely be worked out and forgotten, and then they will start doing something else without evaluating the results, collecting feedback, trying to do things better next time.

In addition, in such a situation, no specialised infrastructure for residencies appears, neither material nor organisational. Rather, the logic of pop-up initiatives dominates here, and this can give little to the institution of the art residency itself.

Why does this temporary approach dominate? Perhaps this is because modern Russian culture is project-oriented. The logic of implementing disparate projects appeared in our cultural policy in the 2000s and today it is still with us. The major grants that you can get for your idea are project-based. That is, the application must contain a clear, defined problem that the project must solve at the end. The support programs themselves are designed for a year and a half. So, you can make a residency with the money from the Vladimir Potanin Foundation or the Presidential Grants Foundation, but at the end of the program, the residency will unlikely have any resources left. At best, it will be possible to find an additional source of income, although it is unlikely to cover all the needs. Therefore, after a short period, such projects stop working — at best, until a new grant is received in the future.

The basis of any residency is its material well-being. And since most residencies rely on only one source of income, they cease to exist as soon as they are deprived of it. Later, they may reappear in a new form, but most likely this will not happen. Therefore, it seems to me that every residency manager should pay attention to strategic planning for their organisation.

Most sustainability specialists focus on the diversification of financial sources. I think it is time to discuss this topic more actively in Russia. At least, residencies may start to think in the direction of introducing commercial activity: the practice of generating income from services is not at all criminal, it is practiced a lot in the UK, for example. Instead of robbing artists, making collections by means of their works, you can sell services: excursions, workshops, lectures. You can open a gift shop or charge fees for certain events or exhibitions. But here, of course, it is necessary to discuss possible options with practitioners: each case may have its limitations.

Kozonina: And to what extent, in your opinion, do the organisers of the residencies themselves want to make their programs more sustainable?

Kim: This is certainly being discussed within organisations, but this discussion has not yet become public, urgent, or large-scale. Residencies are constantly busy with survival, and in such conditions, it can be difficult to think strategically. To think about the future, you first need to satisfy your basic short-term needs. Another problem: we do not have any coaches who could adapt strategies that have already been implemented somewhere for small Russian residencies. Many museums are now opening endowments, which is great and encouraging. In Russia, we rarely plan for a long time, and the work of the endowment is usually associated with a long-term perspective. In the case of residencies, this is a completely different scale. Is it possible to adapt an endowment model to a residency? Is it worth raising such a question? And if it’s not worth it, what other tools can there be? We need good expertise and specialists who can adapt existing strategies to our realities.

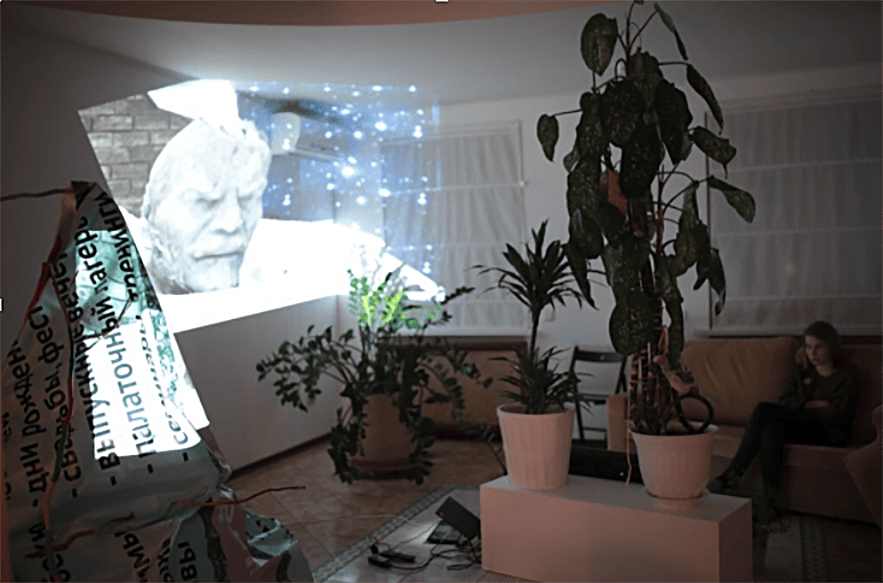

Back Apartment Residency Program participant artist Janessa Clark is giving a workshop at SDVIG space, St. Petersburg, 2019. © CEC ArtsLink

Kozonina: What if we look at the problem of sustainability of residencies from an ecological perspective? Do you think that Russian residencies can function as activators of sustainable development in ecological terms?

Kim: It seems to me that the environmental agenda in Russia is a fairly new phenomenon that has come to the art world along with the interest in the non-human agency, speculative realism, the ‘politics of nature’ (as in the book by Bruno Latour), the social activity of mushrooms, ‘fungi turn’ and so on. But for now, in my opinion, Russian art focuses more on the content of works, rather than on eco-friendly ways of their production. There is often a contradiction between content and implementation, so I would say that this agenda in Russia is still very decorative. I think it will take a long time before environmental thinking is implemented at the infrastructure level, and this will require a huge effort on the part of institutions and residencies.

Russian residencies are still busy with survival: they have no time to think about how they affect the environment. As far as I know from the materials collected for the AiR of Russia website, three or four residency teams are interested in the topic, but it seems that the agenda is not so urgent yet. However, I am quite optimistic: I think that if the discussion arises, then residencies may well become part of it.

Kozonina: What can be an optimistic scenario for the participation of residencies in such a discussion? I mean, in terms of environmental practices. It is clear that since they are public platforms, they can take on an educational function. But is there anything else besides education?

Kim: I’m sure there is. But first, we need to understand that environmental thinking is not only about the content of art, but, first of all, about the organisation of how residencies function. Does it make sense to create a work that tells about environmental issues, but is not eco-friendly in production? Does it make sense to talk about ecology and at the same time support the policy of overproduction in art?

The problem of overproduction in the field of Russian residencies is obvious: the whole field is focused on the rapid change of expositions and constant rotation of artists. This implies a huge number of flights, a tight schedule of work. Few people can endure such an adventure without stress, although the residency activity should concentrate on artists, not on hectic production. I would like to draw attention to the process in which residencies allow art to be created, and there are many levels of working through the problem.

You can offer artists to create works from what they find on the spot instead of purchasing special materials, that is, to apply the recycling logic. And you can think through their stay as much as possible before the visit, reduce the number of trips, and start partnerships only with environmentally conscious companies… This is a different level of discussion, but it is also time to open it.

As for educational function, residencies themselves are places for gathering different specialists, they are creative and intellectual hubs, which, in my opinion, can become platforms for environmental thinking and practice. And here it is not necessary to talk about education. Education is more of a didactic, edifying thing. Rather, I believe in collective creative thinking, and in the idea that art has the potential to explore the world as a whole.

Kozonina: What is your personal interest in participating in this project? What opportunities do you see for yourself as a researcher or practitioner?

Kim: The most important thing for me is to understand the situation in which the residencies exist today. And the topic of sustainability, no matter how fresh it may seem for Russia, can help here. Because it is connected to the theme of responsibility: not only to oneself and artists but also to the society, the environment, and the future. I hope that as a result of this project, new practices will appear, new topical discussions will be initiated. I do not want to engage in didactics, teaching others. I want to articulate problems together and look for solutions. I think this can have a good cumulative effect in the future.