22 Oct 2020

News

Design’s Decade of Self-Criticism

The Post-Fossil Show exhibition features a section which introduces events and activities which took place during the 1960’s in context of Finnish Design. The texts below are by design historian Kaisu Savola.

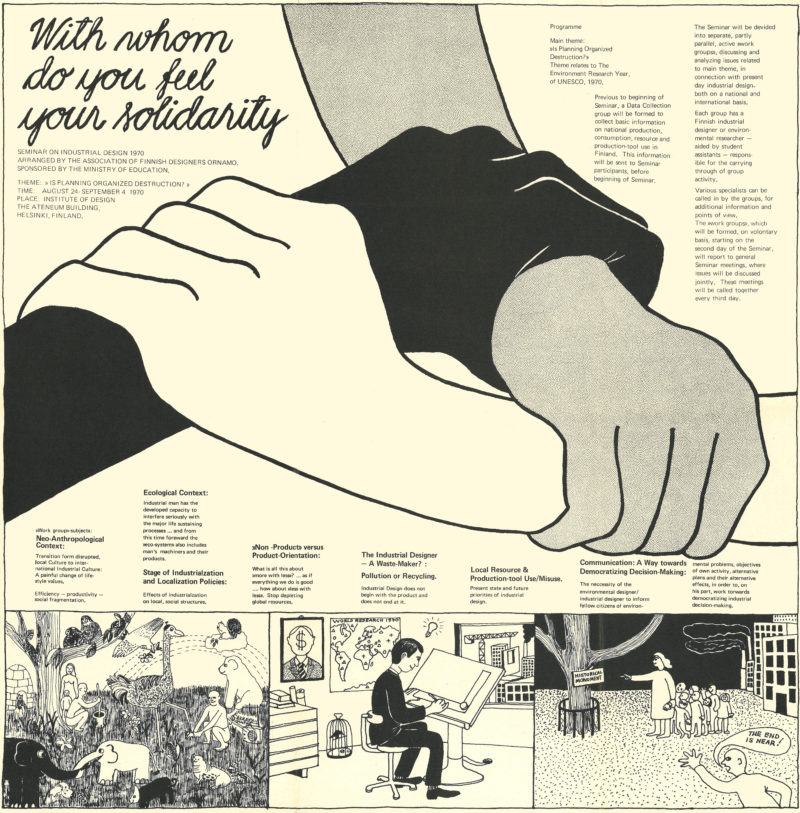

Image: ‘With Whom Do You Feel Your Solidarity’ – an event poster from year 1970, Aalto University archives

Image: ‘With Whom Do You Feel Your Solidarity’ – an event poster from year 1970, Aalto University archives

DESIGN’S DECADE OF SELF-CRITICISM

In 1960, the American journalist Vance Packard published his book Waste Makers, which scandalously revealed the many ways in which the design and advertising industries manipulated the consumer. The aftermath of the book spread across the world, including Finland, where the memory of post-war shortage of food and raw materials was still fresh in people’s minds while the country was developing into a welfare state and Finnish design was gaining global reputation as award-winning objects of exquisite beauty. A new generation of outspoken and idealistic designers began to criticize Finnish design as ‘elitist’, and argued that the pursuit of prizes and awards had diverted the designers from their true responsibilities, which were towards ‘the everyday people’.

In 1962, the professional Association of Finnish Designers, Ornamo, organised a seminar for its members. Most likely inspired by the new critical voices, it was called ‘Days of Self-Criticism’, with the intention of discussing design’s role and purpose in Finnish society and culture. The seminar included a two-day workshop, where the participants were put in groups in order to discuss and debate topical themes related to design, such as the designer’s relationship to society, designer’s moral challenges, freedom and responsibility working as a part of production and marketing, and the cult of the star designer. In the workshop, one group suggested that design should be ‘for all people’, while another reached consensus about designers being ’ideologically naïve’. The same group declared that ’a designer is morally in debt to the society that has supported and fostered him.’ However, what ‘designing for all people’ or being ‘morally in debt’ meant in practice was left undefined.

This kind of culture of self-criticism continued throughout the 1960s and 1970s, reaching some kind of a culmination point in a 1970 design seminar called ‘With whom do you feel your solidarity’. As the poster for the seminar shows, the theme was the provocative question ‘Is planning organized destruction?’. The workshops in the seminar addressed a variety of issues humankind had inflicted on itself and the planet: disruption of eco-systems, destruction of local cultures, waste-making and pollution, and over-production and consumption. Moreover, the programme was increasingly critical over design’s role in causing these problems. Over the course of one decade, the designers’ self-criticism had evolved into questioning the very existence of the discipline.

Images: Children’s playgrounds designed and built by Kaj Franck’s students at Ateneum utilizing recycled materials. Photos from the Helsinki Design Museum Archive.

Images: Children’s playgrounds designed and built by Kaj Franck’s students at Ateneum utilizing recycled materials. Photos from the Helsinki Design Museum Archive.

KAJ FRANCK’S UTOPIA OF ANTI-MATERIAL

‘A new view on a man’s existence is needed, a view not based on material possessions’, Kaj Franck argued in a lecture called ‘The Utopia of Antimaterial’ held in Paris in 1967. Detailing a designer’s contradictory relationship to overproduction and consumption, he continued: ‘A designer feels at the same time both guilty and powerless against the accelerating series of events which by and by break down the scenery of a nature and quickly change it to a new material, conglomerate culture waste heaping up drift-like over our world in the flow of the rivers and in the bottom of the sea. It is true that man has always endeavoured to change nature. But his “slow shaping of daily life” has now been switched on to an automatically functioning system of extracting, producing, distributing, and consuming which cannot be stopped without serious damage to the mechanism of society.’

Although Franck is most famous for his work as a designer, his career as a teacher and design philosopher was equally, if not even more, influential. Franck’s anti-commercial ideology was an intriguing combination of European modernism, Finnish pragmatism and Eastern philosophies encountered during his travels in Asia. During the 1960s, his thinking around design and materialism radicalised further, when debates about over-production and consumption reached Finland.

In his teaching, Franck saw an opportunity to openly question the role that tangible materials play in the design process. In 1966, he asked his students to build temporary shacks for the homeless in Jätkäsaari, then a derelict area on the Helsinki coast line, out of materials claimed from a refuse dump where building companies left their waste. The following year, Franck’s students built a playground for children in a derelict area in Kallio, employing a discarded bus, papier mâché and pastry dough, to name a few. Another assignment asked the students to build sculptures out of snow. The brief emphasized freedom from the pressures of wasting precious material or creating something everlasting. The fact that the works would melt away highlighted the importance of the process and the feelings it evoked in the makers.

Franck’s ‘utopia of antimaterial’ is best summarized in a memory from his childhood which he told upon many occasions, including his lecture in Paris in 1967: ‘When people went out on haymaking, that was in the middle of July, they brought with them to the meadow a round rye-bread with a very hard crust. Out of the crust they cut a round piece and dug out part of the crumb. As much as they needed to fill the hole with the butter they wanted for the bread. Then the round piece of the crust was fitted on again as a cover. An ideal butterbox, which disappeared when the bread was eaten. Not costs, no space and no dirty things to carry home. This butterbox – of air – has been for me the symbol of good design, of functionalism in its most extreme consequence.’

Image: Helsingin Sanomat on 24 May 1966, Helsingin Sanomat archive

Image: Helsingin Sanomat on 24 May 1966, Helsingin Sanomat archive

SCANDAL AT THE INSTITUTE OF INDUSTRIAL ARTS

In the spring of 1966, a group of fourth-year students at the Institute of Industrial Arts were given the task of creating an exhibition presenting the current activities of the school at the Finnish Design Centre gallery in Helsinki. Under the supervision of the school’s art director, designer Kaj Franck, the students put together a showcase of sculptures, images and texts that explored the roles and responsibilities of art education, visual communication and product design in the everyday visual environment. On a late May evening, some minutes before the opening party, the Institute’s rector Markus Visanti ordered the exhibition to be shut down and its contents to be destroyed immediately. In a fit of rage, in front of arriving guests and media representatives, he called the exhibition ‘a communist celebration’ put together by ‘Marxists’. A large and colourful plaster sculpture resembled ‘a sexless egg’ and was therefore to be taken to the landfill. The following day, a bulldozer destroyed the sculpture in the Pitäjänmäki landfill in Helsinki. Eino Jukkanen, operating the bulldozer, saw the plaster crumble into tiny pieces, while the dust disappeared in the landfill air.

The wider audience never saw the exhibition in its original form: it was shut down and a new one was put up in a haste. The students were ordered to mount other work approved by Visanti, but in protest the students simply painted what was left of their original pieces black and exhibited them instead. These, too, were taken down. In the end, the exhibition consisted of photographs showcasing the school’s history and previous students’ works together with future plans of a university status institution dedicated to industrial arts with information of the planned departments and amount of students. Furthermore, Visanti fired three teachers who had supervised the project for showing ‘negligence towards the school and its official politics’. Out of solidarity towards the teachers, Kaj Franck resigned from his post as the Institute’s art director.

The closing of the exhibition, destroying the students’ work and firing the popular teachers caused a big storm in the Finnish mainstream media which published daily reports of the twists and turns of the story. Many reporters and cultural commentators questioned Visanti’s politics and equated his behaviour as censorship. The journalists who had managed to see the exhibition before it was closed did not find any legitimate reason for his reaction, one critic even defending the exhibition calling it ‘very successful and informative in its entirety’.

The original assignment for the students was to present the school and its activities in a way that would convince decision-makers of the benefits of higher education within industrial arts. The students’ interpretation of this was to create an abstract sculpture symbolising three different departments at the Institute: art education, visual environment and product design. A wall of photography depicting the urban everyday life highlighted the importance of the visual in our immediate surroundings. A manifesto-like text declared the artist’s and designer’s responsibility in the creation of the environment and called for a more research-based approach to decision-making instead of blind trust in the artist’s subjective views: ‘More objective results are achieved through teamwork. […] Design is collaboration.’ What Visanti interpreted as ‘Communist’ and ‘Marxist’ was undoubtedly the text’s consumer-critical and anti-commercial views, such as ‘product design is not materialism. […] The goal of design is liberation. […] The designer does not create needs but satisfies them. […] A product is not a status symbol.’ Finally, the students expressed their discontent on the increased focus on industrial design at the cost of craft: ‘there are no boundaries between industry and craft. […] Craft has not lost its purpose in society.’

After the biggest waves of scandal died down, life at the Institute returned to normal. Only some days after the exhibition opening, the fired teachers were given their jobs back and Kaj Franck returned to his position as the art director. However, this incident not only revealed some underlying tensions within the design community, but also started a tumultuous period at the Institute of Industrial Arts, which faced the task of redefining its role and meaning in a changing society. The generational gap and contradictory values between the staff and students did not make this task easier, while the rapid urbanisation and industrialisation taking place in Finland posed new challenges to designers and their education. The contents of the exhibition and the public discussion surrounding the scandal contained many of the key topics in the design debate of the 1960s: design’s social responsibility, anti-consumerism, generational shift, university-level design education and the relationship between industry, design and craft.

The above texts were provided by design historian Kaisu Savola for The Post-Fossil Show exhibition and Po-Fo Reader. The texts employ primary sources from the Aalto University Archive and the Helsinki Design Museum Archive. Kaisu is currently working on her doctoral thesis (coming up in spring 2021) focusing on social and political ideologies in Finnish design in the 60s and 70s.